|

| Soil |

Farmers have selectively cultivated plants for thousands of years, choosing a plant, for example, based on its ability to survive certain conditions or on how many seeds it produces.

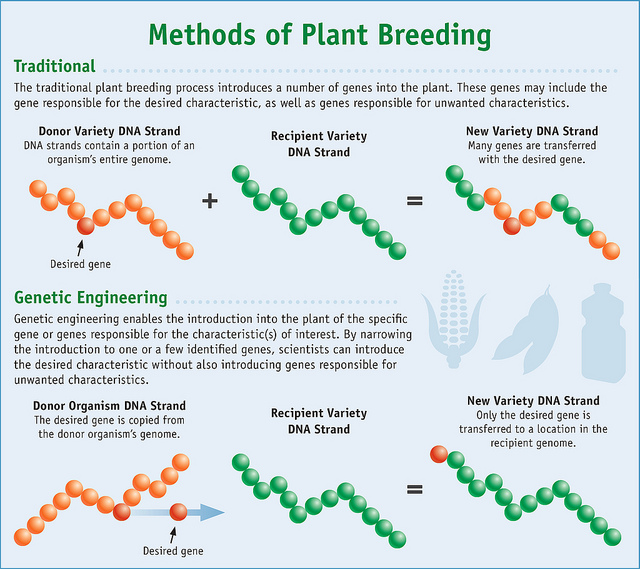

Farmers also sought to improve plants by crossing them with related species that had other desirable characteristics. This type of selective, or traditional, breeding involves crossing thousands of genes. Genetically modified organisms are the product of a targeted process where a few select genes are transferred into a plant to produce a desired trait.

When scientists create a genetically modified plant, the process begins by identifying a desired trait. That trait may be resistance to an insect or the ability to tolerate drought conditions. Scientists look for those genes in nature by seeking other organisms, including other plants and microbes, which exhibit the trait they want to express in a genetically modified plant. Once they have identified a trait and isolated the specific gene or genes that control the trait, the next step in development is to transfer the desired gene into a crop plant.

The improved plant is then extensively tested, and researchers look for differences between the GM plant and its conventional counterpart. Just as with other breeding methods, plants that do not perform are not selected to move through the development process and will not reach the market. GM plant “performance” includes meeting stringent safety testing requirements.

Before a GMO plant reaches the market, more than 75 different studies are performed on genetically modified crops to ensure they are safe for people, animals, and the environment. This data is reviewed by up to three regulatory agencies in the U.S. - USDA, EPA and FDA – and the GM plant must be approved by these agencies before it can be commercialized. Global regulatory agencies in more than 75 countries have reviewed the safety of genetically modified crops and have found no risk.

Watch this video to learn more about this process.

History of Crop Modification

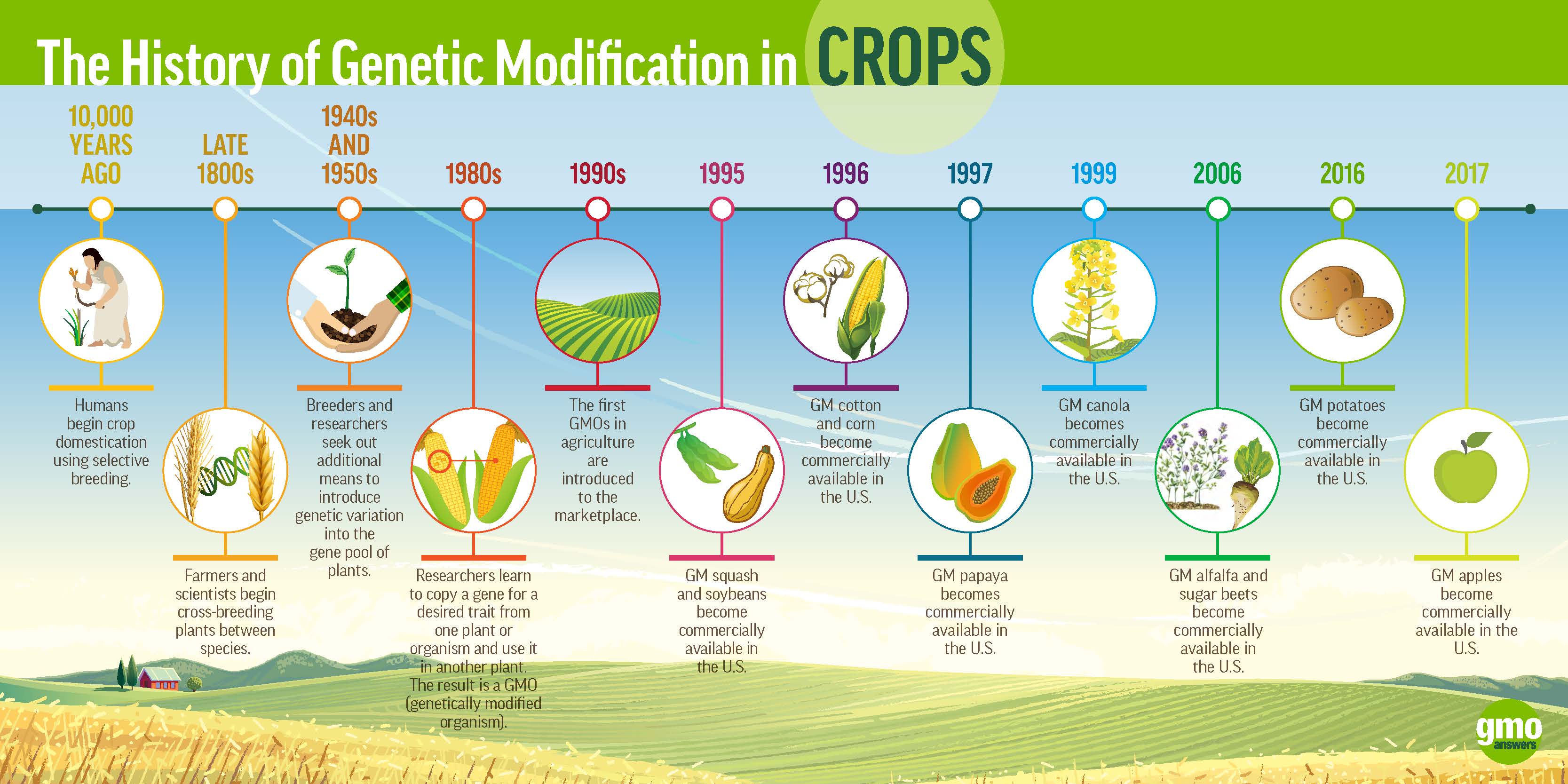

Farmers have intentionally changed the genetic makeup of all crops they have grown and the livestock they have raised since domestic agriculture began 10,000 years ago. Every fruit, vegetable and grain that is commercially available today has been genetically altered through human intervention and selective breeding, including organic and heirloom seeds. Plant breeding began centuries ago when farmers selectively crossed plants to develop enhanced seed varieties. There are many breeding techniques used to develop seeds for modern agriculture, and they are often grouped into three categories.

Each of these techniques may be used to develop a new plant variety, sometimes in a continuum over many years. For example, seeds developed through selective breeding may be altered again through mutagenesis and then altered again using genetic engineering.

- Selective Breeding (“traditional breeding”): Early plant breeders looked for and cross-bred plants that had the characteristics they wanted. They have crossed plants within a species and across species beginning thousands of years ago. Traditional breeding of different grass species led to the development, over time, of modern corn from its teosinte ancestor. And today’s bread wheat was created by crossing, over time, at least 11 different species.

- Mutagenesis (“mutation breeding”): Beginning in the 1920s, breeders started seeking more diversity than they were able to achieve through selective breeding to create new traits. They began to make changes in plant DNA by exposing seeds to chemicals or gamma irradiation and then selecting the plants that displayed the traits they wanted. More than 3,200 varieties of commonly consumed plant products have been developed using mutagenesis, including varieties of red grapefruit, bananas, peanuts, peppermint and rice.

- Genetic Engineering (“GMO”): In the late 20th century, advances in technology enabled us to expand the genetic diversity of crops. For years, university, government and company scientists intensively researched and refined this process. A major result has been genetically modified seeds that maintain or increase the yield of crops while requiring less land and fewer inputs, both of which lessen the impact of agriculture on the environment and reduce costs for farmers.

While selective breeding and mutagenesis methods usually involve crossing or altering thousands of genes, genetic engineering enables breeders to select a trait or characteristic that exists in nature and insert the associated gene(s) into the target plant. Genetic engineering also allows a breeder to make changes in a plant’s makeup without any insertions whatsoever, for example, by silencing (“turning off”) existing genes.

So far, there are only 10 commercialized GMO crops in the United States, but there are other genetically modified plants approved in other countries, with many more in development here and around the world, including cassava, cowpea, pineapple, sorghum, tomatoes and wheat.

For more information on international approvals, visit the GM Approval Database at ISAAA.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment